IRDs can lead to a future marked by vision loss

Inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) are a group of rare genetic conditions affecting the retina caused by at least 1 gene not working as it should. The most common type of IRD is retinitis pigmentosa (RP), affecting 1 in 3,000-4,000 individuals worldwide. Often progressive, IRDs can lead to severe vision loss and even legal blindness over time. IRDs impact the functional vision your patients depend on every day, such as in daily activities, social relationships, and work and school life.1-4

On average, an IRD diagnosis for patients can take5:

8

Doctor visits

Up to

7

years

Diagnosing IRDs can be an odyssey for patients

The IRD diagnostic journey is commonly described as an “odyssey” due to numerous challenges. These include navigating referrals to different specialists, undergoing comprehensive evaluations using various methods, and encountering obstacles within the healthcare system.6

I was wearing glasses at age 2. As I got older, I was severely nearsighted and had astigmatism. In my 30s, I went in for an exam and was diagnosed with RP.

– Brenda, living with an IRD

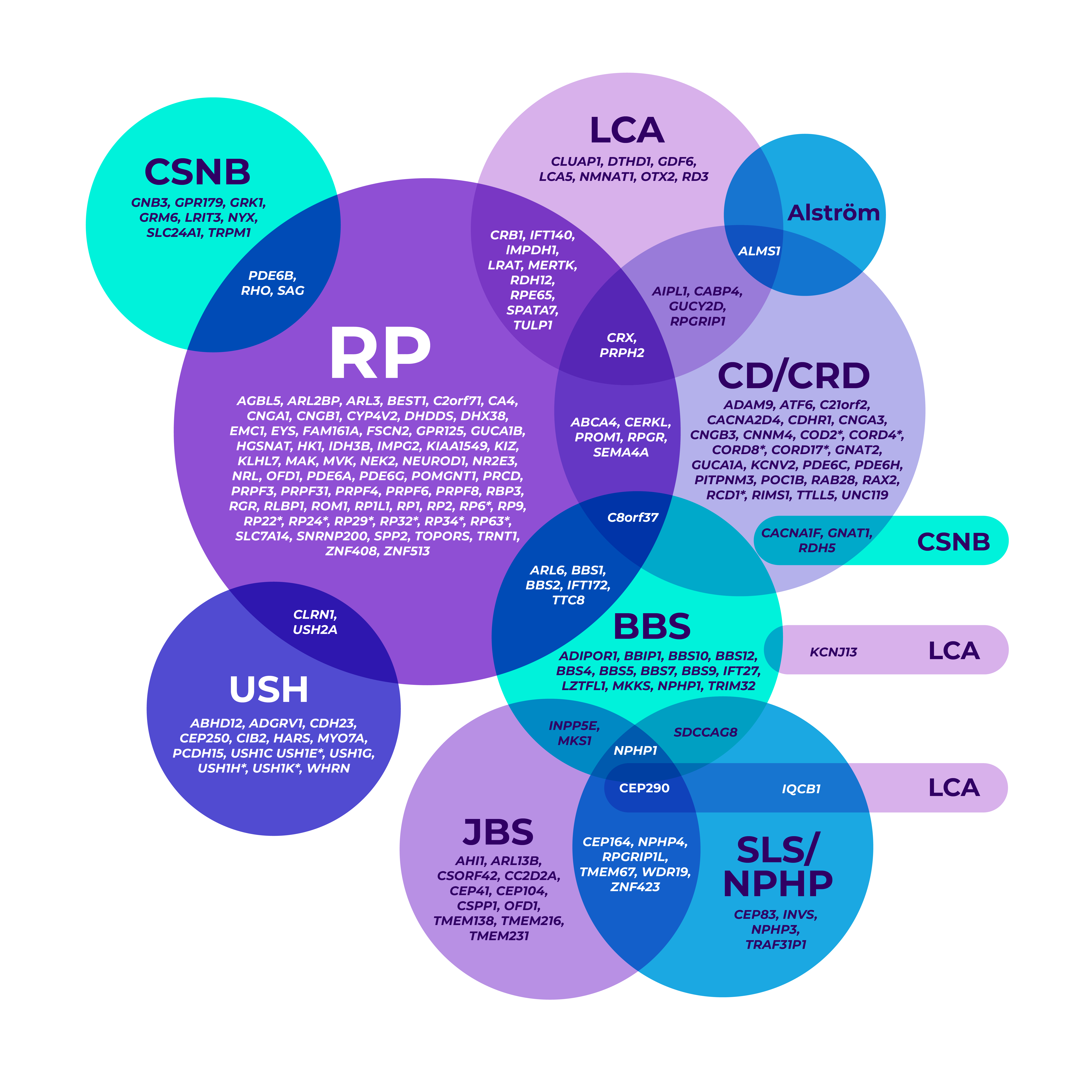

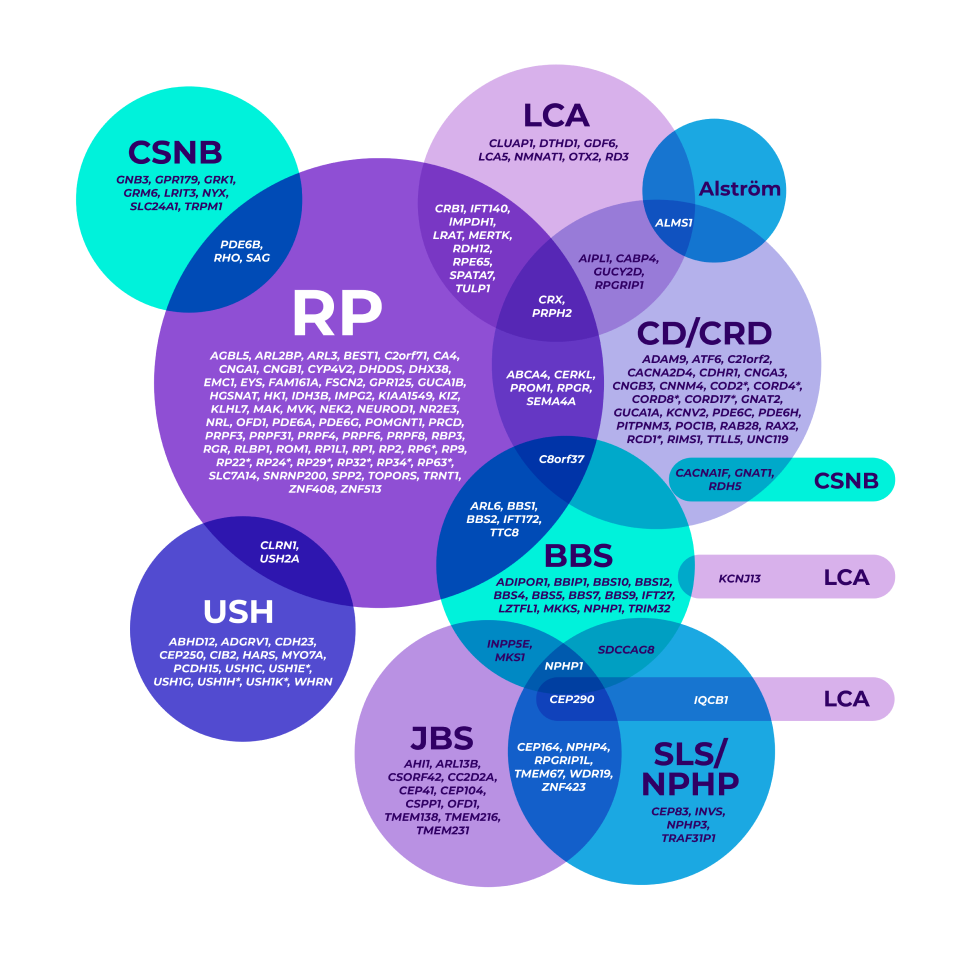

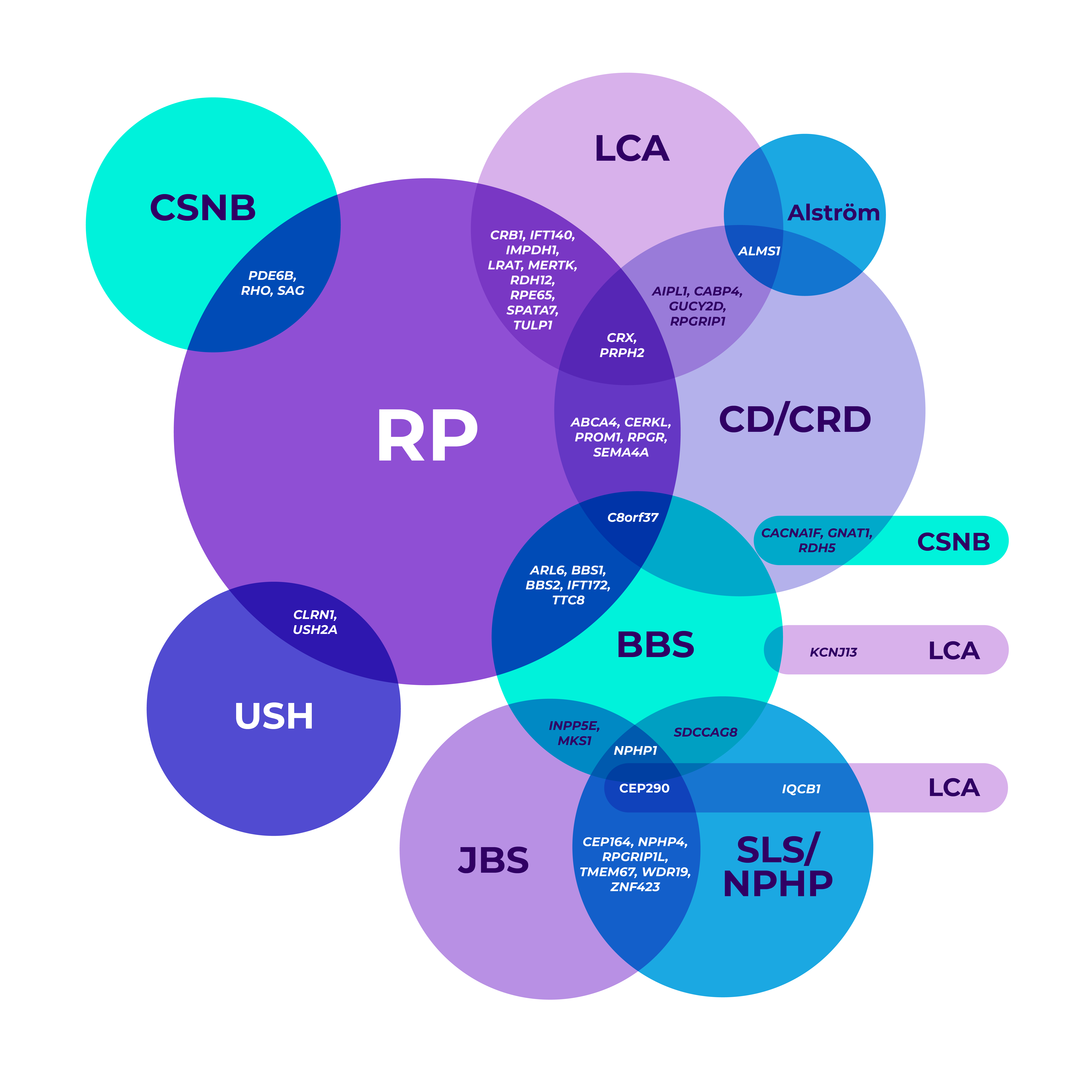

Explore the overlapping challenges of IRDs

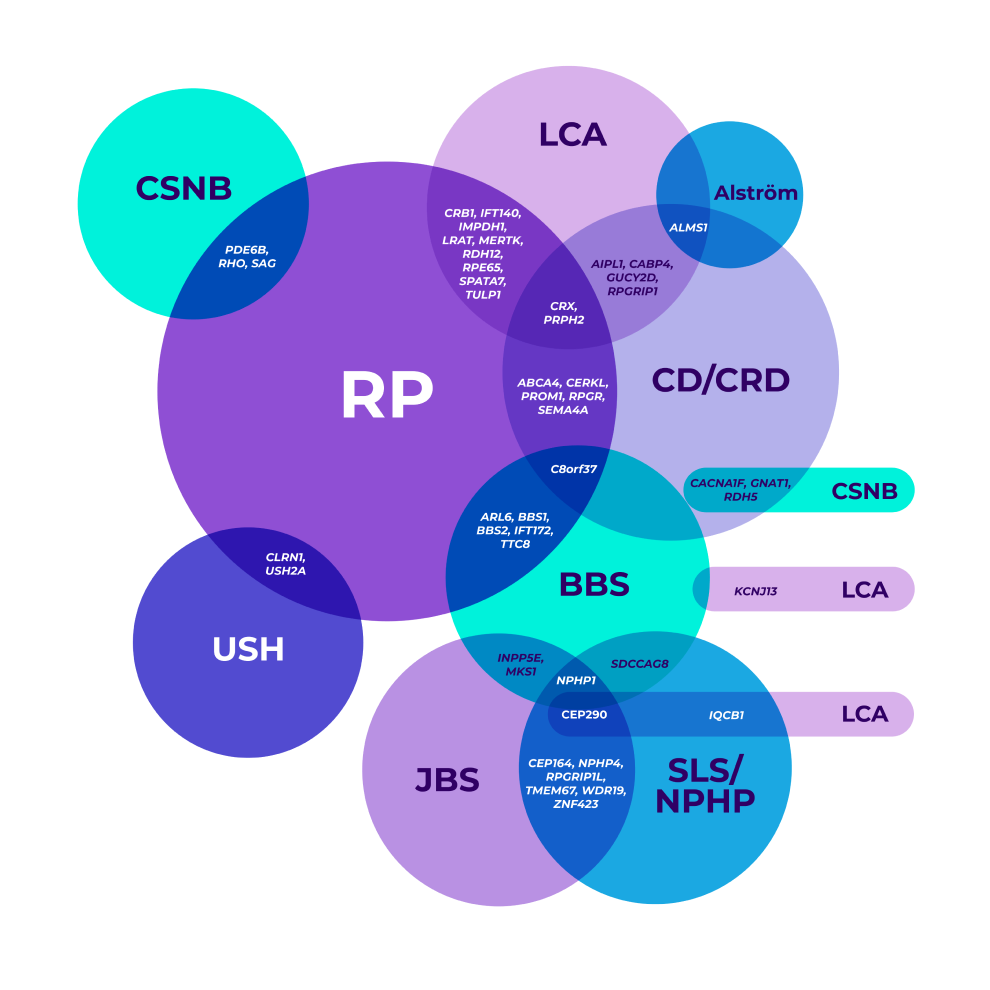

The genetic heterogeneity of IRDs can make it clinically challenging to reach a specific diagnosis, leading to delayed diagnoses. A single gene may even be associated with multiple phenotypes.7-9

*Mapped genetic loci without an identified gene, as of 2019.

©2021 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Reproduced with permission.

BBS=Bardet-Biedl syndrome; CD=cone dystrophy; CRD=cone-rod dystrophy; CSNB=congenital stationary night blindness; JBS=Joubert syndrome; LCA=Leber congenital amaurosis; NPHP=nephronophthisis; RP=retinitis pigmentosa; SLS=Senior-Løken syndrome; USH=Usher syndrome.

Genetic testing supports clinical findings and is becoming the standard for reaching an accurate diagnosis, which can help inform future medical management.7,8

Early genetic testing matters

According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, early genetic testing7,8,10:

Provides a more accurate diagnosis sooner, guiding optimal future medical decisions and informing family planning

Is required to determine eligibility for approved gene therapy

Overlapping gene variants8

Genetic testing helped confirm a more precise diagnosis in a patient who presented with nonspecific signs and symptoms.

The AMERICAN ACADEMY OF OPHTHALMOLOGY recommends genetic testing for most patients with a suspected IRD8

Take a closer look at some IRDs: signs, symptoms, and prevalence

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP)11

Signs and symptoms may include

- Night blindness (earliest symptom)

- Blind spots develop in the peripheral vision; over time, these blind spots merge to produce tunnel vision

- Loss of central vision over time

Age of onset

Presents in childhood or early adulthood

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 4,000*

*In the United States and Europe.

X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (XLRP)2,3,11-13A subset of RP

A subset of RP

Signs and symptoms may include

- Males experience earlier and more severe symptoms than females

- Early night blindness

- Peripheral vision loss (tunnel vision)

- Accidents, including falls or bumping into objects

- Rapid decline of vision, resulting in legal blindness by third or fourth decade

Almost all males with an RPGR variant will exhibit symptoms of XLRP, and 40% of female carriers show baseline abnormalities in their vision tests.

Age of onset

Early onset

Estimated prevalence

XLRP is a subtype of RP. 5%-15% of people diagnosed with RP have XLRP.

- RPGR, RP2, and ODF1 are 3 genes in which mutations can cause XLRP

- RPGR variants are responsible for 70%-90% of all XLRP cases

Over time, XLRP can significantly impact your patients’ functional vision, the usable vision they depend on to perform everyday activities.

Usher syndrome (USH)14-16

Signs and symptoms may include

- Partial or total hearing loss and vision loss over time

- Loss of night vision occurs first

- Blind spots merge to produce tunnel vision over time

- Three different clinical types (I, II, and III) with variable symptom severity and presentation

Age of onset

Presents at birth (Usher syndrome type I, type II), or by adolescence or adulthood (Usher syndrome type III)

Estimated prevalence

About 1 in 25,000*

*Prevalence rate reflects US population.

Stargardt disease17

Signs and symptoms may include

- Slow, progressive loss of central vision

- Color blindness

- Light sensitivity

Age of onset

Presents in late childhood to early adulthood

Estimated prevalence

About 1 in 6,500

Cone-rod dystrophy (CRD)18

Signs and symptoms may include

- Decreased visual acuity

- Photophobia

- Loss of color vision

- Scotomas

- Loss of peripheral vision

- Legal blindness by mid-adulthood

Age of onset

Presents in childhood

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 30,000

Achromatopsia (ACHM)19

Signs and symptoms may include

- Partial or total absence of color vision

- Can only see black, white, and shades of gray

- Photophobia

- Nystagmus

- Reduced visual acuity

- Hyperopia

Age of onset

Presents at birth or early infancy

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 30,000

Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA)20,21

Signs and symptoms may include

- Reduced vision (at birth to early infancy)

- Photophobia

- Nystagmus

- Hyperopia

- Keratoconus

- Franceschetti’s oculo-digital sign (eye poking, pressing, and rubbing)

Age of onset

Usually presents at infancy

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 33,000

Choroideremia (CHM)22

Signs and symptoms may include

- Progressive atrophy of the outer retina and inner choroid

- Night blindness in early childhood

- Progressive loss of peripheral visual field and visual acuity

- All individuals will develop blindness, most commonly in late adulthood

Age of onset

Usually presents in early childhood

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 50,000

Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS)23,24

Signs and symptoms may include

- Night blindness

- Blind spots merge to produce tunnel vision over time

- Blurred central vision

- Legally blind by adolescence or early adulthood

- Renal malformations

- Obesity

- Postaxial polydactyly

- Hypogonadism

- Developmental delays

Age of onset

Ocular symptoms present in first decade of life

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 140,000

While BBS is one of the rarest IRDs, its prevalence may be higher in some geographic regions

Disclaimer: All prevalence rates are global estimates and may vary across regions.